This article was first published in the June 2020 edition of National Eczema Society’s membership magazine, Exchange.

Supporting a child with eczema is highly challenging and the healthcare system does not always make it easier. Fiona Cowdell, Professor of Nursing and Health Research at Birmingham City University, has been researching new ways to help families manage the condition more easily.

Eczema affects around one in five children in the UK and is one of the 50 most burdensome diseases globally. Most people with eczema are treated by GPs but consultations are often unsatisfactory, for patients and practitioners alike.

Part of the challenge is that eczema requires considerable self-management at home, often supported by family members – and it is not easy.

Regular and consistent application of emollients can be challenging and many parents are concerned about using steroid creams. Treatment failure is common, often because parents are given little advice on how and when to use prescribed treatments. But self-management is vital if parents are to ‘get control and keep control’ of their child’s eczema.

The Mindlines study

In 2016 I was awarded a four-year, part-time National Institute for Health Research

Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellowship to investigate new ways to improve treatment of childhood eczema in primary care. At its simplest, ‘knowledge mobilisation’ is moving knowledge to where it is most useful.

The study – called the Mindlines study – aims to find new ways to improve primary care consultations, with GPs, health visitors and community pharmacists, and support more effective self-management of childhood eczema. My particular interest is in people who are least likely to access eczema information: the so-called hard-to-reach groups.

Knowledge about the best ways to treat childhood eczema already exists – for example, in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management. However, GPs, health visitors and community pharmacists do not always use this guidance and parents may well not know about it.

The study has involved lay people (including people with eczema and parents of children

with the condition), practitioners (GPs and trainee GPs, health visitors, practice nurses, community pharmacists, pharmacy counter assistants, dermatology specialist nurses and dermatologists), researchers, and other stakeholders, such as the National Eczema Society.

The research process

The research has comprised four phases.

In PHASE 1, I spent several months observing consultations in primary care. I particularly noticed how few patients attended with eczema as the main reason for their appointment. Very often it was mentioned just as the consultation ended.

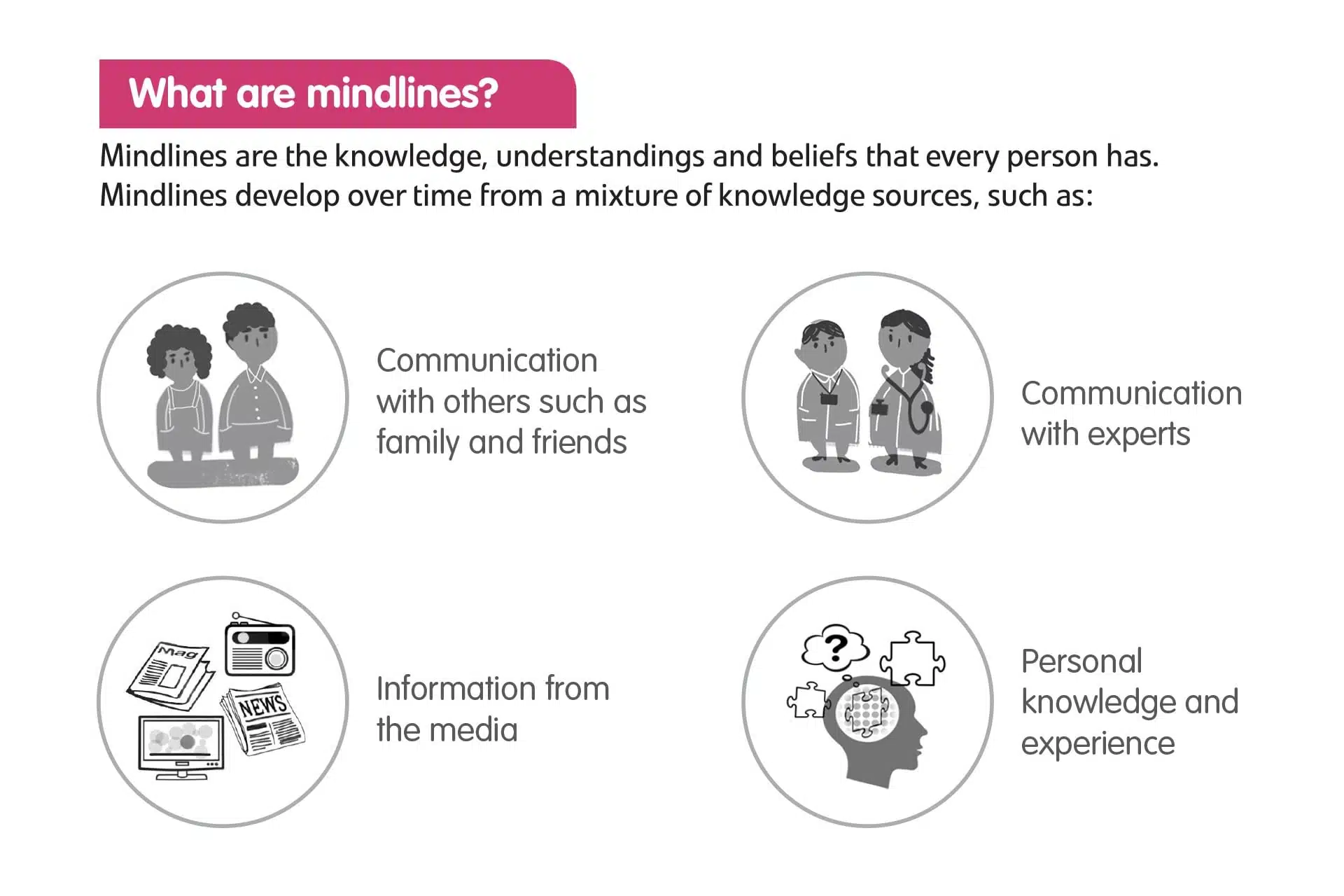

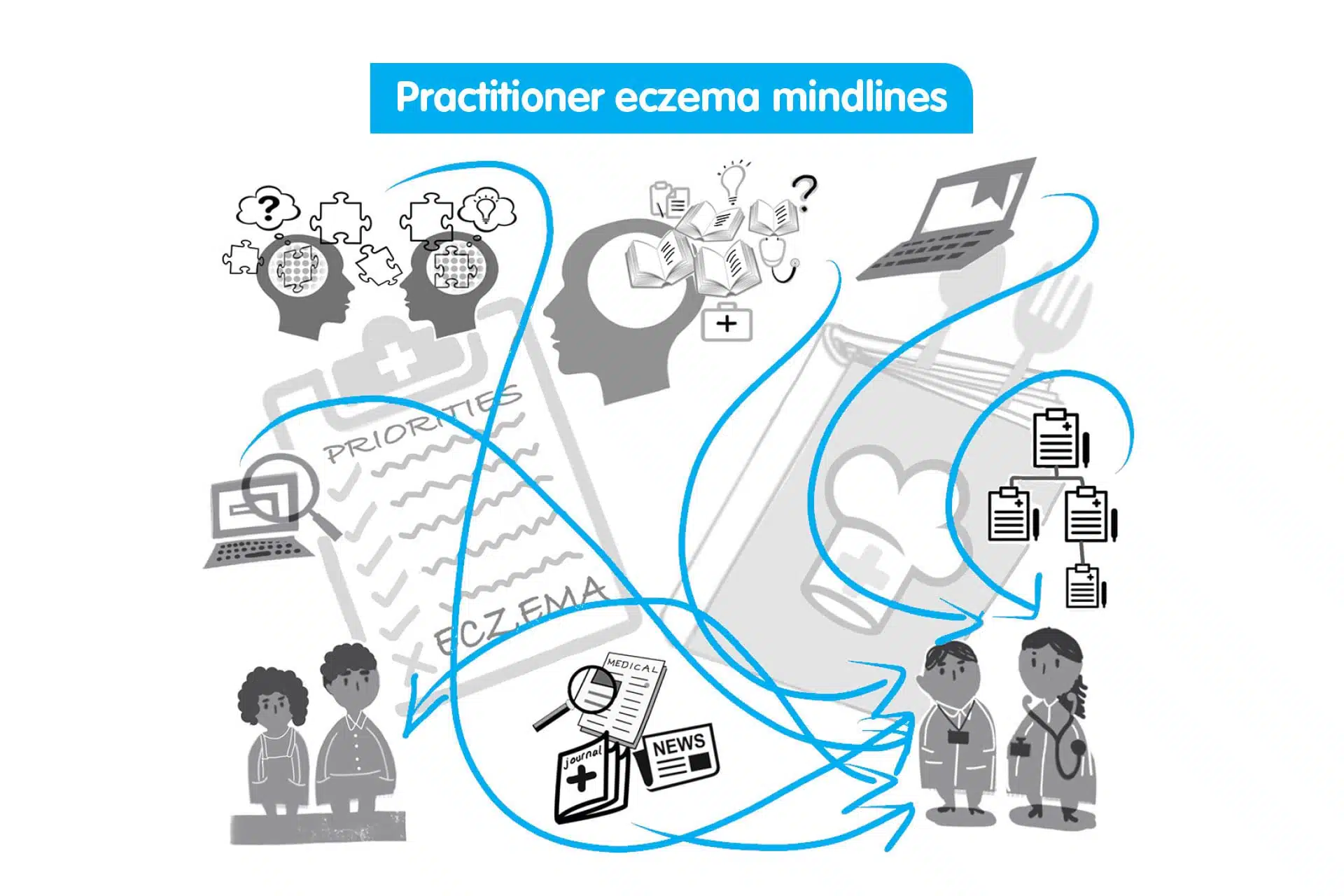

I also interviewed parents of children with eczema, young people with eczema, GPs and trainee GPs, health visitors, practice nurses, community pharmacists and pharmacy-counter assistants, to understand how their eczema mindlines had developed. Then a colleague produced illustrations of lay and practitioner mindlines.

In PHASE 2, I interviewed another group (similar to those in Phase 1) and shared the mindlines illustrations. I asked if they made sense to them, and whether their mindlines had developed similarly. Then we adjusted the illustrations.

As I expected, I found that lay people and practitioners construct their eczema mindlines from a whole range of sources. However, there were differences between the two.

For practitioners, eczema was a relatively low-priority condition. They thought that treatment had not changed much over time so the need to update their knowledge was limited. They often made treatment decisions based on local prescribing guidelines.

In contrast, lay people learnt a significant amount through a dispiriting process of trial and error and by listening to (sometimes inaccurate) information from others. They thought that practitioners did not always take eczema seriously and underestimated its impact on children and families.

Once I knew more about eczema mindlines, PHASE 3 involved finding new ways to revise or modify existing mindlines by adding reliable and useful knowledge and erasing outdated or inaccurate information.

To do this, I brought together a group of 22 people, including parents of children with eczema, young people with eczema, GPs and trainee GPs, health visitors, practice nurses, community pharmacists and pharmacy counter assistants and dermatology specialist nurses to co-create ways to change mindlines.

The group recognised the critical relationship between lay and practitioner mindlines. For this reason, they suggested modifying lay and practitioner mindlines in parallel. They also recognised the need to inform influential people in wider society – for example, grandparents, teachers and nursery staff. The group in most need of new knowledge were those hard-to-reach people who were least likely to access information.

The co-creation group thought the most effective way to reach the target groups and achieved shared knowledge and understanding was through sharing simple, consistent information directed to everyone who influences eczema care.

The information needed to come from trusted people, and should be easy to access, short, practical, relevant to individuals, and easy to act on. The main message was ‘Small change, big difference’.

Five agreed messages were:

- Eczema is more than just dry skin.

- Eczema doesn’t just go away.

- Moisturisers are for every day.

- Steroid creams are okay when you need them.

- You know your child’s eczema best.

Each of these messages is linked to further information and we produced materials including postcards, short animations and a website with a link to the National Eczema Society website at: www.bcu.ac.uk/research/-centres-of-excellence/centre-for-health-and-social-care-research/projects/eczema-mindlines

The final phase, PHASE 4, is still in progress. This involves sharing the five core messages in

one small area of an inner city, using a whole range of approaches (pictured below), including:

- a shopping centre drop-in, hosting around 90 consultations in one day.

- storytime at nursey, infant an primary schools.

- displays at community pharmacies.

- displays at GP surgeries.

- interactive sessions for GPs, nurses and health visitors.

- events at places of worship.

- posting on Twitter.

The aim is to reach as many people as possible in a small area, in the hope that messages would get to everyone involved. I am now working on evaluating how effective we have been in sharing these messages.

What this work means to me

I hope the five messages will support a shared understanding of eczema and the basics of treatment among parents of children with eczema, young people with the condition, practitioners and wider social influencers. This should also improve consultations and help people self-manage as effectively as possible.

For many years I worked as a nurse in clinical practice, often seeing people living with eczema. I am aware of excellent eczema research, but mindful that there is still a need to address the basics of care. There are many people for whom eczema is not a priority, but who still suffer with it. Some are unlikely to actively seek information but their condition may be improved through getting simple messages to them.

The enjoyment in this work has been through working with a whole range of people, including lay people, practitioners and researchers, to find new ways to share straightforward messages that may improve eczema care.

The Fellowship ends in May 2020 and I’m now seeking more funding to share the five messages with children across the UK, through music and reading, as well as working with other research teams on improving care of childhood eczema.

FIONA COWDELL is funded by a National Institute for Health Research Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellowship. This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.